System Constraint (Bottleneck) (Dialogue Part 2)

Question: Last time we ended the conversation with the idea that the essence of TOC is to find the core problem of a company, but a "regular" company has so many different problems! I wouldn't say that any one of them is the only and main issue – usually, several need to be addressed simultaneously.

Georg: Do you agree that every business (system) exists only because it purchases (or receives) some "raw material" and transforms it, adding value that the customer is willing to pay money for?

J: Please explain what you mean by that?

G: Okay, let's start with examples:

a) A furniture manufacturer buys wood and turns it into shelves or chairs, ideally ones that the customer is willing to pay more for than the raw materials cost.

b) The store I shop at buys just the cheese and bread I like, along with "Pinot Grigio" from my favorite winemaker, delivers it to me at a convenient location, and I pay them much more than the raw materials cost.

c) Your hairdresser sits you down in their chair and cuts your hair, but in a very unique way. It may not make much sense to me, but it seems like you pay him a good amount for the "added value" to your head.

J: Okay, okay! I agree with the idea of transforming raw materials into added value. But now, please explain the main problem.

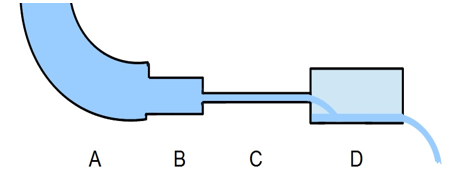

G: Here's the key conclusion in your phrase about transforming raw materials: a business process always has a defined main direction – from cheaper raw materials to higher added value. Let's call this the business or process flow. A flow is also a specific physical concept – there are air, water, electron, magnetic, and other flows in different systems. Look below at the diagram of a pipeline, where you can see the direction of the water flow. Tell me, what prevents us from getting more water at the right (higher value-added) end of the pipe?

J: I think it's the section C, the smallest diameter pipe.

G: So, if we’ve built a water supply system like this, then its ability to deliver more added value is limited by the flow rate of the section C pipe?

J: Yes!

G: Let's assume that our system has many issues – for example, section A has a small leak, section B has thinner walls than the others, and section D could use a paint job. As we can see, there are many problems in the system, and they all need to be addressed. Which one would you tackle first?

J: Well, don’t be silly – of course, section C!

G: You've identified the main problem of the system – the one limiting the system from achieving the highest possible throughput or added value. By the way, you’ve also disproven your earlier statement that multiple problems in the system (company) must be addressed at once.

J: Your example is about a simple technical system, but what about a company or organization?

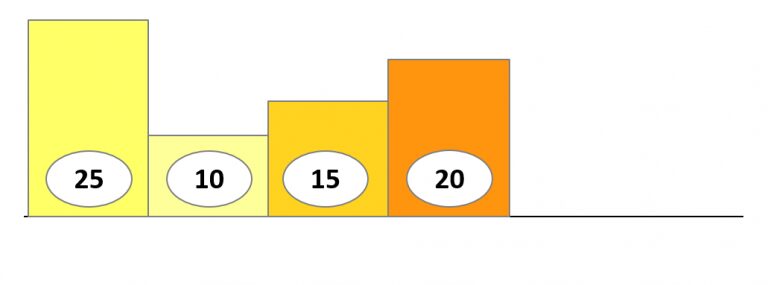

G: Okay, let’s start with a manufacturing company. In diagram 4.1, I’ve sketched out the internal flow (process) of such a company. Each column represents a work station, each capable of processing a certain number of parts per hour (which is indicated on each column), and then passing them on for further processing. Do you see any bottleneck or main issue in this system that limits the flow or the throughput? What maximum result can this system produce? How many finished products can the company sell to its customers?

J: The operation with a capacity of 10 parts per hour limits the entire system’s throughput, so the company won’t be able to produce more and thus can’t sell more than 10 parts per hour.

G: You're absolutely right! (See diagram 4.2.) By the way, thanks for using the term "throughput." It’s one of the official TOC terms we’ll be using going forward. In English, it’s called “Throughput” (T), and its official definition is: throughput (T) is the rate at which a system generates money through sales. In our example, 10 parts per hour is not quite throughput yet; it's just a measure of potential sales pace. However, if we knew that the added value of each product is, say, 100 euros, the throughput in this case would be 100×10=1000 euros per hour.

J: Sales pace, throughput…

G: I see I’ve gone too deep into definitions and numbers, so I’ll explain where the term "throughput" came from in Latvian. When I was preparing Thomas Corbett’s book "TOC Accounting" for publication in Latvian last winter and received the translation from the publisher, I noticed that the translator had used at least three variants for the term “Throughput” in Latvian – "caurlaide," "caurplūde," and "caurlaidspēja." The translator probably didn’t think it was important to keep a consistent term, but wanted it to sound better in context.

I called one of Latvia’s leading TOC experts, Pauls Irbins, and after a long discussion, we agreed that from now on, the term in Latvian will be “caurlaide.” One of the arguments was that in the first Latvian edition of E. Goldratt's book "The Goal," the term "caurlaide" was used as well.

I agree it’s not a very pleasant term, but as a consolation, I’ll mention that in some cases in Russian literature on TOC, the translation “Проход” is used, which sounds even worse and resembles something from proctology.

Okay, now let’s go back to our four-workstation company. You’ve successfully identified the system’s bottleneck (in English – System Constraints). To increase the system’s throughput (T), which means increasing the overall value added by the system simultaneously, we’ll make improvements and increase the throughput of the bottleneck station (which processes 10 parts per hour) to 20 parts per hour. How will the overall system’s sales pace change?

J: Well, of course, it will increase from 10 to 20 parts per hour! Although no, looking at your diagram, it seems like it will increase only to 15 parts per hour, because now we have a new bottleneck with a throughput of 15 parts per hour.

G: Exactly! In diagram 4.3, you can see the new system status, where we increased the bottleneck throughput by 100%, but as a result, we can only achieve a 50% increase in sales pace. Now, if we invested more resources into system improvement and increased the throughput of the last section (which processes 25 parts per hour) to 50 parts per hour, how much would the overall system throughput or sales pace increase?

J: I think it wouldn’t increase at all, because the last section isn’t the system’s bottleneck.

G: Wait a minute, what did you just say? That by making process improvements, investing in "innovations" and similar activities in a section or process that isn’t the system’s bottleneck, we might end up wasting money?

J: Oddly, it seems exactly that way. At least now I begin to understand what happened in my practice. There was a case when we took out a loan and bought a new piece of equipment with twice the productivity of the old one. All the calculations showed that this equipment would pay off within a reasonable time and start generating profits. However, it turned out that we didn’t see any increase in profits at all! Of course, there were many discussions and explanations – someone said we should load the equipment with three shifts instead of two, someone criticized the sales team for not finding customers for this specific machine – you know how it goes. Now I begin to understand how it was possible to work even with the lower productivity of the old machine. Back then, it wasn’t even the system’s bottleneck!

G: Your case is very typical; you can find such examples in many companies. At least I’ve seen so many expensive pieces of equipment (boys love new toys) that, at best, didn’t live up to expectations, and in the worst case, were working 24 hours a day, turning a lot of money into unnecessary inventory of semi-finished products. It’s even more tragic with the most modern software, which is bought because the existing one is supposedly outdated and can’t ensure a dramatic increase in turnover and thus greater profits. After implementation, you hear that the new system is much faster, more user-friendly, has more options, and provides more ways to get the necessary information in different angles, etc.

Try asking the business owner the classic question from Goldratt’s book "The Goal" after a new investment project has been realized: "Has your company’s turnover and profit drastically increased now?" You’ll see a strange look of confusion in the respondent’s eyes: "Not exactly, but now we work much more efficiently!"

Then comes the second question with the risk of losing the conversation partner: "You work much more efficiently, but turnover and profit didn’t increase with the implementation of the new system. So, did you reduce the number of employees?"

At this point, it’s better to end the discussion (the character in Goldratt’s book starts rushing to catch a plane), because the business owner suddenly starts analyzing what happened: "We invested to increase profit, but we got something entirely different. Why did this happen?" In the second case, the conversation partner begins desperately looking for arguments to defend their position, which will cause inner unrest.

J: Are you really against new technologies and equipment?

G: Of course not! But investments should only be made once the system’s (company's) main goal is formulated, the system’s constraint is identified, and all the simple methods of expanding the constraint’s throughput are exhausted. Then, you should invest in expanding the constraint and moving towards achieving the system’s main goal.

J: That sounds like some kind of method or recipe.

G: Yes, we have finally arrived at one of the fundamental cornerstones of TOC solutions, which is called:

The Five Focusing Steps (5FS):

- Identify the system's constraint.

- Decide how to exploit the system’s constraint.

- Subordinate everything else to the decision.

- Elevate the system’s constraint.

- If the system’s constraint is broken, return to the first step (identify the system's constraint), but don’t allow inertia to create a new system constraint.

J: That sounds pretty serious. Can you explain?

G: Yes, these are the five focusing steps developed by Goldratt, and every word in this formula has meaning. To make it easier, we can look again at our pipeline (drawing No. 3) or our production system (drawing No. 4.1), which, from the system’s perspective, look very similar.

J: Yes, it’s the same: stages A, B, C, and D with a similar throughput structure.

G: Exactly! Now, let’s look at the first step: identifying the system’s constraint. You’ve already done that; it’s stage C. The second step is deciding how to exploit the system’s constraint. What are your suggestions for maximally exploiting stage C?

J: If we’re talking about a pipe with such a diameter… Maybe we could clean it so there are no deposits?

G: Good idea! But what about the production system’s stage C?

J: Clean it too. No, it’s not related to cleanliness.

G: You think so? What flows through the pipe, and what creates resistance due to deposits?

J: Deposits slow down the water flow. Yes, there’s a flow in the production process, but what could slow it down? Perhaps additional work done by operators, including administrative, transport, etc., or equipment downtime during lunch breaks, or something else?

G: You’re on the right track. If we carefully examined the process, we would find many "deposits" that have accumulated over time. This is why step three follows – subordinate everything else. What is that "everything else" in this process that could reduce the throughput at stage C?

J: If someone places a cork in our pipeline before stage C or shuts off the water entirely, but in a production system, it could be something that halts or slows down the flow, right?

G: Exactly, the operation of all other stages must be subordinated so that there is always a sufficient flow before and after the system’s constraint. In production, this means that materials and semi-finished products used at stage C must always be available in sufficient quantities and of good quality. If there’s a risk that stage C might need repairs at some point, it should be done immediately and at maximum speed, even if it means stopping work at other stages, etc.

J: The fourth step is to elevate the system’s throughput.

G: That means, despite the throughput improvements we’ve made, stage C might still be the system's constraint. So, it's time to take radical steps (new or additional equipment, dividing the stage, and other techniques we won’t discuss today) and increase the throughput of the stage so that it is no longer the system's constraint.

The fifth step states that after all our work, the system now has greater throughput, which increases the company’s revenue and/or profit. Now it’s time to look for a new system constraint, because we can definitely achieve much more.

I could highlight today’s conclusions:

- EVERY PROCESS (BUSINESS) IS BASED ON A FLOW THAT INCREASES THE VALUE OF RAW MATERIALS.

- EVERY PROCESS HAS A CONSTRAINT THAT LIMITS THE SYSTEM’S THROUGHPUT.

- THE SYSTEM’S OVERALL THROUGHPUT CANNOT BE LARGER THAN THE THROUGHPUT OF THE SYSTEM’S CONSTRAINT.

- IMPROVING OR INCREASING THE THROUGHPUT OF ANY OTHER STAGE (NOT THE SYSTEM’S CONSTRAINT) DOES NOT INCREASE THE OVERALL THROUGHPUT OF THE SYSTEM.

Also, today we’ve looked at how Goldratt’s Five Focusing Steps (5FS) work.

P.S. Reader, if you disagree with any of these conclusions or something is unclear, write your comment or question in the "Contacts" section.

In the next “Dialog”: Practical recommendations on using 5FS (how to identify, exploit, and subordinate).