System Constraint (Bottleneck) (Dialogue Part 2)

Question: Last time we ended the conversation with the idea that the essence of TOC is to find the core problem of a company, but a "regular" company has so many different problems! I wouldn't say that any one of them is the only and main issue – usually, several need to be addressed simultaneously.

Georg: Do you agree that every business (system) exists only because it purchases (or receives) some "raw material" and transforms it, adding value that the customer is willing to pay money for?

J: Please explain what you mean by that?

G: Okay, let's start with examples:

a) A furniture manufacturer buys wood and turns it into shelves or chairs, ideally ones that the customer is willing to pay more for than the raw materials cost.

b) The store I shop at buys just the cheese and bread I like, along with "Pinot Grigio" from my favorite winemaker, delivers it to me at a convenient location, and I pay them much more than the raw materials cost.

c) Your hairdresser sits you down in their chair and cuts your hair, but in a very unique way. It may not make much sense to me, but it seems like you pay him a good amount for the "added value" to your head.

J: Okay, okay! I agree with the idea of transforming raw materials into added value. But now, please explain the main problem.

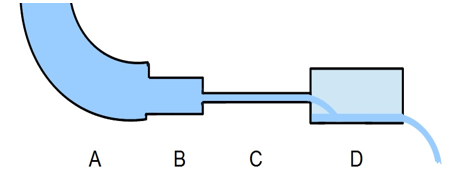

G: Here's the key conclusion in your phrase about transforming raw materials: a business process always has a defined main direction – from cheaper raw materials to higher added value. Let's call this the business or process flow. A flow is also a specific physical concept – there are air, water, electron, magnetic, and other flows in different systems. Look below at the diagram of a pipeline, where you can see the direction of the water flow. Tell me, what prevents us from getting more water at the right (higher value-added) end of the pipe?

J: I think it's the section C, the smallest diameter pipe.

G: So, if we’ve built a water supply system like this, then its ability to deliver more added value is limited by the flow rate of the section C pipe?

J: Yes!

G: Let's assume that our system has many issues – for example, section A has a small leak, section B has thinner walls than the others, and section D could use a paint job. As we can see, there are many problems in the system, and they all need to be addressed. Which one would you tackle first?

J: Well, don’t be silly – of course, section C!

G: You've identified the main problem of the system – the one limiting the system from achieving the highest possible throughput or added value. By the way, you’ve also disproven your earlier statement that multiple problems in the system (company) must be addressed at once.

J: Your example is about a simple technical system, but what about a company or organization?

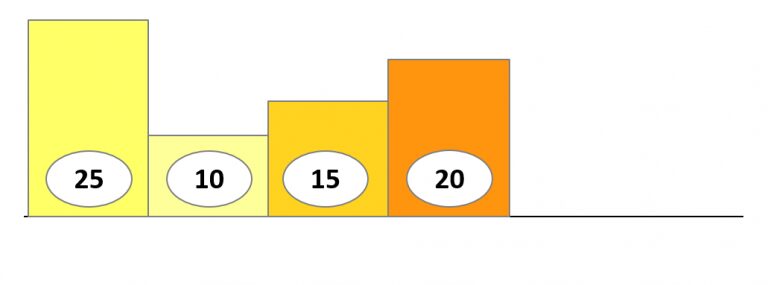

G: Okay, let’s start with a manufacturing company. In diagram 4.1, I’ve sketched out the internal flow (process) of such a company. Each column represents a work station, each capable of processing a certain number of parts per hour (which is indicated on each column), and then passing them on for further processing. Do you see any bottleneck or main issue in this system that limits the flow or the throughput? What maximum result can this system produce? How many finished products can the company sell to its customers?

J: The operation with a capacity of 10 parts per hour limits the entire system’s throughput, so the company won’t be able to produce more and thus can’t sell more than 10 parts per hour.

G: You're absolutely right! (See diagram 4.2.) By the way, thanks for using the term "throughput." It’s one of the official TOC terms we’ll be using going forward. In English, it’s called “Throughput” (T), and its official definition is: throughput (T) is the rate at which a system generates money through sales. In our example, 10 parts per hour is not quite throughput yet; it's just a measure of potential sales pace. However, if we knew that the added value of each product is, say, 100 euros, the throughput in this case would be 100×10=1000 euros per hour.

J: Sales pace, throughput…

G: I see I’ve gone too deep into definitions and numbers, so I’ll explain where the term "throughput" came from in Latvian. When I was preparing Thomas Corbett’s book "TOC Accounting" for publication in Latvian last winter and received the translation from the publisher, I noticed that the translator had used at least three variants for the term “Throughput” in Latvian – "caurlaide," "caurplūde," and "caurlaidspēja." The translator probably didn’t think it was important to keep a consistent term, but wanted it to sound better in context.

I called one of Latvia’s leading TOC experts, Pauls Irbins, and after a long discussion, we agreed that from now on, the term in Latvian will be “caurlaide.” One of the arguments was that in the first Latvian edition of E. Goldratt's book "The Goal," the term "caurlaide" was used as well.

I agree it’s not a very pleasant term, but as a consolation, I’ll mention that in some cases in Russian literature on TOC, the translation “Проход” is used, which sounds even worse and resembles something from proctology.

Okay, now let’s go back to our four-workstation company. You’ve successfully identified the system’s bottleneck (in English – System Constraints). To increase the system’s throughput (T), which means increasing the overall value added by the system simultaneously, we’ll make improvements and increase the throughput of the bottleneck station (which processes 10 parts per hour) to 20 parts per hour. How will the overall system’s sales pace change?

J: Well, of course, it will increase from 10 to 20 parts per hour! Although no, looking at your diagram, it seems like it will increase only to 15 parts per hour, because now we have a new bottleneck with a throughput of 15 parts per hour.

G: Exactly! In diagram 4.3, you can see the new system status, where we increased the bottleneck throughput by 100%, but as a result, we can only achieve a 50% increase in sales pace. Now, if we invested more resources into system improvement and increased the throughput of the last section (which processes 25 parts per hour) to 50 parts per hour, how much would the overall system throughput or sales pace increase?

J: I think it wouldn’t increase at all, because the last section isn’t the system’s bottleneck.

G: Wait a minute, what did you just say? That by making process improvements, investing in "innovations" and similar activities in a section or process that isn’t the system’s bottleneck, we might end up wasting money?

J: Oddly, it seems exactly that way. At least now I begin to understand what happened in my practice. There was a case when we took out a loan and bought a new piece of equipment with twice the productivity of the old one. All the calculations showed that this equipment would pay off within a reasonable time and start generating profits. However, it turned out that we didn’t see any increase in profits at all! Of course, there were many discussions and explanations – someone said we should load the equipment with three shifts instead of two, someone criticized the sales team for not finding customers for this specific machine – you know how it goes. Now I begin to understand how it was possible to work even with the lower productivity of the old machine. Back then, it wasn’t even the system’s bottleneck!

G: Your case is very typical; you can find such examples in many companies. At least I’ve seen so many expensive pieces of equipment (boys love new toys) that, at best, didn’t live up to expectations, and in the worst case, were working 24 hours a day, turning a lot of money into unnecessary inventory of semi-finished products. It’s even more tragic with the most modern software, which is bought because the existing one is supposedly outdated and can’t ensure a dramatic increase in turnover and thus greater profits. After implementation, you hear that the new system is much faster, more user-friendly, has more options, and provides more ways to get the necessary information in different angles, etc.

Try asking the business owner the classic question from Goldratt’s book "The Goal" after a new investment project has been realized: "Has your company’s turnover and profit drastically increased now?" You’ll see a strange look of confusion in the respondent’s eyes: "Not exactly, but now we work much more efficiently!"

Then comes the second question with the risk of losing the conversation partner: "You work much more efficiently, but turnover and profit didn’t increase with the implementation of the new system. So, did you reduce the number of employees?"

At this point, it’s better to end the discussion (the character in Goldratt’s book starts rushing to catch a plane), because the business owner suddenly starts analyzing what happened: "We invested to increase profit, but we got something entirely different. Why did this happen?" In the second case, the conversation partner begins desperately looking for arguments to defend their position, which will cause inner unrest.

J: Are you really against new technologies and equipment?

G: Of course not! But investments should only be made once the system’s (company's) main goal is formulated, the system’s constraint is identified, and all the simple methods of expanding the constraint’s throughput are exhausted. Then, you should invest in expanding the constraint and moving towards achieving the system’s main goal.

J: That sounds like some kind of method or recipe.

G: Yes, we have finally arrived at one of the fundamental cornerstones of TOC solutions, which is called:

The Five Focusing Steps (5FS):

- Identify the system's constraint.

- Decide how to exploit the system’s constraint.

- Subordinate everything else to the decision.

- Elevate the system’s constraint.

- If the system’s constraint is broken, return to the first step (identify the system's constraint), but don’t allow inertia to create a new system constraint.

J: That sounds pretty serious. Can you explain?

G: Yes, these are the five focusing steps developed by Goldratt, and every word in this formula has meaning. To make it easier, we can look again at our pipeline (drawing No. 3) or our production system (drawing No. 4.1), which, from the system’s perspective, look very similar.

J: Yes, it’s the same: stages A, B, C, and D with a similar throughput structure.

G: Exactly! Now, let’s look at the first step: identifying the system’s constraint. You’ve already done that; it’s stage C. The second step is deciding how to exploit the system’s constraint. What are your suggestions for maximally exploiting stage C?

J: If we’re talking about a pipe with such a diameter… Maybe we could clean it so there are no deposits?

G: Good idea! But what about the production system’s stage C?

J: Clean it too. No, it’s not related to cleanliness.

G: You think so? What flows through the pipe, and what creates resistance due to deposits?

J: Deposits slow down the water flow. Yes, there’s a flow in the production process, but what could slow it down? Perhaps additional work done by operators, including administrative, transport, etc., or equipment downtime during lunch breaks, or something else?

G: You’re on the right track. If we carefully examined the process, we would find many "deposits" that have accumulated over time. This is why step three follows – subordinate everything else. What is that "everything else" in this process that could reduce the throughput at stage C?

J: If someone places a cork in our pipeline before stage C or shuts off the water entirely, but in a production system, it could be something that halts or slows down the flow, right?

G: Exactly, the operation of all other stages must be subordinated so that there is always a sufficient flow before and after the system’s constraint. In production, this means that materials and semi-finished products used at stage C must always be available in sufficient quantities and of good quality. If there’s a risk that stage C might need repairs at some point, it should be done immediately and at maximum speed, even if it means stopping work at other stages, etc.

J: The fourth step is to elevate the system’s throughput.

G: That means, despite the throughput improvements we’ve made, stage C might still be the system's constraint. So, it's time to take radical steps (new or additional equipment, dividing the stage, and other techniques we won’t discuss today) and increase the throughput of the stage so that it is no longer the system's constraint.

The fifth step states that after all our work, the system now has greater throughput, which increases the company’s revenue and/or profit. Now it’s time to look for a new system constraint, because we can definitely achieve much more.

I could highlight today’s conclusions:

- EVERY PROCESS (BUSINESS) IS BASED ON A FLOW THAT INCREASES THE VALUE OF RAW MATERIALS.

- EVERY PROCESS HAS A CONSTRAINT THAT LIMITS THE SYSTEM’S THROUGHPUT.

- THE SYSTEM’S OVERALL THROUGHPUT CANNOT BE LARGER THAN THE THROUGHPUT OF THE SYSTEM’S CONSTRAINT.

- IMPROVING OR INCREASING THE THROUGHPUT OF ANY OTHER STAGE (NOT THE SYSTEM’S CONSTRAINT) DOES NOT INCREASE THE OVERALL THROUGHPUT OF THE SYSTEM.

Also, today we’ve looked at how Goldratt’s Five Focusing Steps (5FS) work.

P.S. Reader, if you disagree with any of these conclusions or something is unclear, write your comment or question in the "Contacts" section.

In the next “Dialog”: Practical recommendations on using 5FS (how to identify, exploit, and subordinate).

Theory of Constraints and Coffee (Dialogue Part 1)

Question: When and how did the Theory of Constraints (TOC) arise?

George's answer: The official beginning of the theory can be considered the year 1984 when Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt published his first book, "The Goal". Unlike Lean philosophy, whose roots lie in Zen Buddhism, TOC's foundations are based on analytical scientific approaches to problem-solving. All TOC conclusions can be proven logically and mathematically.

Q: What connection do constraints and theories have to my practical daily problems?

G: Even among TOC experts, there are ongoing debates that this name might discourage entrepreneurs, as they may think it’s something complex and distant from reality. The name TOC will probably forever remain as a popular brand, but one of the main principles of TOC is: every system, no matter how complicated it seems, has an inherent internal simplicity.

Q: My business is very complex, there are many departments, employees, many suppliers, and very peculiar clients – what simplicity is there?

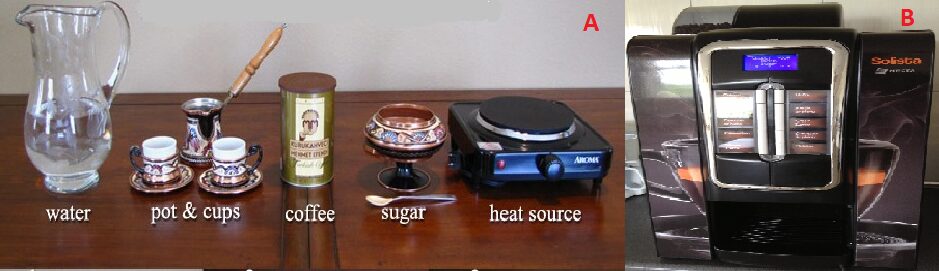

G: Look at the pictures: which of the two coffee-making systems is simpler, A or B?

If you ask this question to anyone on the street, you’ll probably get the answer: "Of course, A, because I can hardly imagine how many pipes, mechanisms, and electronics are inside B!"

But if you ask the same question to a scientist or a TOC specialist, the answer will be: "No doubt, B, because to make coffee, especially the one I want, you only need to press one button (espresso, cappuccino, latte, etc.), but with A, I have to do many actions, and the result is not guaranteed!"

In other words, the simpler management system is the one that requires controlling the smallest number of elements to achieve the desired result.

We don’t need to get into discussions about coffee flavor differences or the cost of maintaining the equipment. We all are excellent experts in generating various “buts”. Everything has its time, we’ll talk about that later.

But imagine how it would be if you could create a business that could be managed with two buttons: "Profit" and "Big profit". Press the chosen button, and immediately feel exactly the flavor you’ve desired.

Q: That’s pure fantasy – without effort, sweat, and work, you can't achieve anything!

G: Okay, let’s assume that to build a "Profit Machine," you would have to work hard for two to three years (maybe a lot of sweat too – although I don’t like that), but the "button" would be pretty stiff, and to press it all the way, you would need the constant cooperation of several people. Does it look more realistic now?

Q: You’ve seen my business and say that from today’s situation to big profit it’s possible to reach in two to three years? No, business always moves step by step, even very small steps.

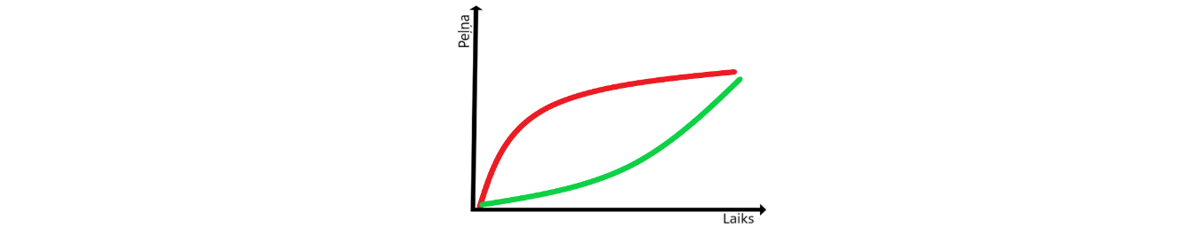

G: Here are two possible development paths for the company – the Green and Red lines. Which one do you think reflects a good business development plan?

Q: I think the green one. That’s usually how development plans for companies look. For example, if you bring a business plan to a bank with a Red line, you have no chance – they’ll reject it as unrealistic!

G: Well, you’re right about banks, they always offer an umbrella when the sun is shining, but will snatch it out of your hands as soon as the rain starts!

However, if we look at the development paths of the world’s best, most profitable companies, and not only Google, Facebook, or Apple, but also thousands of smaller, less popular companies, they are all on the Red development line. We can take as an example the 500 largest companies in Latvia. I’m sure you’ll find a significant portion of them on a pronounced Red line, despite the post-crisis situation.

Of course, most companies follow the Green line, but some of them are so green that it looks like a pine needle path. Do you want to choose this road?

Q: Yes, I need to think about that! But you haven’t yet explained how this is related to TOC?

G: The idea of small, incremental improvements is very popular and allows justifying any improvements, even if they lead to real problems for the company. Moreover, this idea is rooted deep in the cultural and mental paradigms that have been cultivated for centuries and are very hard to overcome. The method of small, constant improvements can only be considered a short-term deep defense policy until the system’s (company’s) core problem (that "button" that needs to be built and pressed) is understood. The longer you delay addressing the company’s main problem, the higher the likelihood that soon this company, with you or any other manager, won’t have any problems left, as all the issues will be in the hands of a bankruptcy administrator. TOC teaches and explains exactly how to identify the core problem of the system and how to quickly solve it, leading the company along the red development line.

Can we agree that you see the possibility that:

- EVERY SYSTEM HAS INHERENT INTERNAL SIMPLICITY.

- THE FEWER POINTS IN A SYSTEM THAT IMPACT THE RESULT – THE SIMPLER IT IS (and this does not depend on whether we can describe the system’s construction on one page or if it requires 100GB).

- A SUCCESSFUL COMPANY CAN DEVELOP VERY RAPIDLY (along the Red line), and this naturally happens to all successful companies. And that means there are methods to achieve this.

Q: It looks like I’ll have to agree!

What to do with employees during uncertain times?

Not everything we encounter can be changed, but nothing can be changed until we have encountered it.

— James Baldwin

I have received feedback and questions after publishing the previous blog (How to Act in Times of Uncertainty?). Some of them are from abroad. Therefore, I want to clarify that the situation described is based on the situation in Latvia (as of April 3), which is different from what is happening in other countries. For example, at this point, industrial enterprises and construction activities, as well as the functioning of stores and restaurants (maximizing remote work and adhering to sanitary and social distancing rules), are not prohibited here. At the same time, all entertainment, cultural, sports, training, and other activities that involve gatherings of people are prohibited.

I would like to share some thoughts, based on frequently asked questions.

Question: What should we do with employees in these times?

Answer: Take maximum care of them! Not only because people have humanity, and business leaders are people, too, usually wise and experienced in life (even if there are doubts about a particular case…). Not only because you – as a leader – may know about possible problems your employees are facing or family tragedies that your decision might cause. But also because your employees are one of your company’s most important resources. Losing them is easy, growing and training new ones is difficult and expensive. It sounds cliché, but let’s think a little deeper.

What does “expensive” mean? What do you lose by laying off your employees, and what will you have to pay to restore the previous situation after the crisis?

Already now, the company will have to pay money related to employee layoffs. Such actions automatically create a “black wave” within the company. Depending on the level of layoffs, this wave can turn into a tsunami, which will destroy the culture your company has built for a long time.

It will automatically make the remaining employees seriously think about their chances of continuing to work here and other possible options. Thoughts will shift from your company’s survival and the prospects for future growth to a distant future.

Some of you may offer employees the option to receive unemployment benefits and come back when the situation improves. This might work for some. However, judging by the experience of 2009, when you start gathering the team again, you may find that your best “experts” have already found other jobs!

The logic is simple. Whenever your employee receives another tempting offer, they compare the potential benefit with the potential risk of losing their current job. There is always a price for this. By “temporarily laying off” employees, you immediately remove this risk from the equation. They are already unemployed! Therefore, the risk for the employee in accepting a new offer is “0”. But even if you offer them to return after the crisis, you will have to offer something much more tempting and pay a much higher price to get them to risk and leave their new job!

After the crisis, surviving B and C type companies (see How to Act in Times of Uncertainty?) will face a new challenge. At this point, some of your competitors may no longer be active. However, there will be others who are much stronger and better prepared for the “low start” than you! The rating of all suppliers in the eyes of your clients will change rapidly. Will you be at the top of this ranking?

That depends on whether you can quickly offer your clients exactly the value-added services (VAS) they need! At this point, one of the main criteria for value-added services will be the ability to deliver the required quantity, but faster (and with longer payment terms)! Of course, quality, service levels, and other VAS criteria will also be important. But “faster” will be much more important than before.

How can you ensure faster delivery of increased volumes? Perhaps you have maintained all the equipment and technologies. However, you no longer have several specialists who can perform the necessary work and ensure the required production capacity.

Let’s assume that the crisis is coming to an end, some of your competitors sharply increase their offers, come up with new attractive deals, and start earning a lot of money.

Your business survived during the crisis, but now it could “die” during the growth phase! To prevent that from happening, you urgently need to restore your business’s “humanitarian capacity”.

This means – urgently searching for new employees.

The first problem is that while simpler workers may be found quickly, finding specialists will take longer. Will these employees prove to be good enough? You’ll find that out, perhaps during the probation period or later. It is clear that no employee will be ready to work exactly in your company, with your technologies, products, rules, and internal culture. Employee training and adaptation will take time.

I offer one theoretical thought chain (example):

Attracting mid-level specialists.

Time from decision-making to hiring – 1-3 months.

Training and adaptation time, when their productivity and contribution to the company is on average 50% (0-90%) – 1-3 months.

In addition, there is the possibility that the specialist will turn out to be unsuitable for the position – 10% (?).

Other employees’ time spent training the specialist, costs for organizing the workplace, work clothing, social packages, etc.

As a result, in this example, without the layoff money, you would need to pay 3-4 months’ salary to return to the previous humanitarian capacity level. But the worst part is that there will be several months when you will still lack capacity, and the company will not be able to make a breakthrough and will lose real orders and money.

This also means that you may lose some clients who will go to “faster” competitors!

Conclusion: In this example, with a crisis duration of 5-6 months, it would be more cost-effective for the company to keep such specialists than to lay them off.

Of course, this is possible if the company has reserves or a more or less regular cash flow. How to control, measure, and how important it is to maintain it was discussed earlier (see How to Act in Times of Uncertainty?).

You need to search for and use all possible assistance mechanisms available during this time (state unemployment benefits, possible credit instruments, etc.).

Question: Does this mean the company should pay employees for doing nothing?

Answer: No! This reduced activity time is perfect for doing what you didn’t have time for in previous years! I remind you that this is for B and C type companies, which are still working in some form, better or worse. A type companies are closed, they don’t operate, and there’s no other option but to reduce all possible maintenance costs, including laying off employees…

Moreover, this needs to be done quickly. “The worst thing is to cut a dog’s tail into small pieces”.

In my course, I created 3 tools to be used when there’s a shortage of labor (and at the time it seemed the most important!) and 6 tools for when the company lacks work. These can be revisited today.

Five tools for utilizing workforce in a "soft situation":

- Use time to improve processes, reduce lead-time.

- Use time to increase technological reserve capacity (RC).

- Use time to create the necessary VHRK (Virtual Humanitarian Reserve Capacity).

- Convert HRK into increased throughput (T).

- Use time to create △Reserves.

In this article, I will explain only the third – creating VHRK. Many companies’ policies focus on deep specialization of employees, dividing them into departments, sections, and shifts. Employees with deep specialization are valued and do not “interfere with others’ tasks”. A frequently heard conversation in manufacturing companies: “We are short of 3-4 welders (assemblers, painters, etc.), yet the company employs 100-150 workers.” This means that at any given time, this company is short of some welders, but always has excess workers! By definition, no company can have a perfectly balanced specialist composition at any given moment. There are always changes in the order structure, product specifics, people get sick, take vacations, etc.

The principle of creating VHRK is to abandon deep specialization and move towards employee skills universalization. This means that there are 100 employees in the company, but at the same time, there are 200 or 300 different (and varying levels of) specialists! And the company’s culture is such that each of them is ready to switch to a different task and understands the benefits for both themselves and the company.

This time is great for dedicating time to employee training, building VHRK within the company. This will allow, once activities are revived, to quickly increase product volumes for products that will be in high demand at that time!

And another technique already used among entrepreneurs is “employee lending”.

There are companies working in different industries. Some have spare workers, while others are short on them. It’s possible, by making the appropriate agreement, to lend employee capacity to the company that currently needs it. Replacing the “every man for himself” strategy with a win-win situation, solving both companies’ problems and giving people an opportunity to earn.

Usually, this applies to simpler workers. But it is possible that many of them might have other qualifications that are currently underutilized.

I think a new option might appear for higher-level specialists as well.

Let me explain. There are several companies that have stopped operating. These companies have highly qualified specialists who are hoping for a potential business revival after the crisis. Perhaps these companies’ leaders don’t want to lay off their best specialists, but at the same time cannot pay them the previous amount of money.

On the other hand, there are many companies that are successfully operating during this time, and demand for their products is rising sharply. However, they are making many mistakes and showing unprofessionalism, such as in quality, service, customer service, etc. Could it be possible to start “lending” specialists from one company to another? For example, the specialist would work 2 days a week for one company and 3 days a week for the second. Companies should make their deals so that everyone would benefit and receive their slice of profit. In such situations, when specialists are absolutely “necessary” for both companies, the use of talent can lead to mutual advantages.

Dear colleagues, HR company leaders, isn’t it true that the one who can organize this type of business information and specialist exchange will gain new opportunities for their own business as well?

Take care of people, and they will take care of your business.

― John Maxwell

About the blog

Usually, entrepreneurs don’t have time to read thick books or listen to long lectures because they spend their entire day “saving” their business. That’s why we want answers to our questions here and now. If that doesn’t happen, we continue working as “firefighters” for our company’s problems, often without even realizing that today’s battle only slightly subdued the flames, and tomorrow the fire may grow even stronger elsewhere.

We don’t even have time to think about the root causes of our problems and how to solve them once and for a long time. These are exactly the kind of issues that TOC tackles.

Knowing that I am one of the few TOC specialists in Latvia, my colleagues, acquaintances, and entrepreneurs I meet at various events ask me practical questions about business management. Some of them are very deep and professional, while others seem simple but remain unclear.

To help at least a few entrepreneurs discover the incredible opportunities TOC offers—and to do so without requiring much of their time—I have decided to start publishing a dialogue about TOC. I will write it in parts so that reading each new section doesn’t take much time and can be completed in about ten minutes.

The dialogue will be based on various questions, with answers grounded in TOC knowledge. At first, it will be a discussion about the fundamentals of TOC, but how the conversation develops depends on you, the reader! Feel free to ask questions about what you have read, what you want to understand, or what you disagree with, because moving forward, we may use conclusions from previous discussions as a foundation for future dialogues.

How to operate in times of uncertainty?

In Times Like These, It’s Good to Remember That There Have Always Been Times Like These.

— Paul Harvey

Everything that has happened in the past few weeks has placed us all in a completely new situation. It could be a fundamental shift in the way people will live in the future. But such changes frequently occur in human history. This might be the greatest economic stress the world has experienced in the last 70 years. However, the economic system is highly resilient, and sooner or later, this crisis will pass. Unfortunately, not all businesses will survive. Survival is never guaranteed…

In recent days, several colleagues—businesses I have consulted or teams we have trained—have reached out to us. The questions I hear are certainly relevant to many.

That’s why I’ve decided to share some recommendations for navigating this situation.

First and Foremost: The TOC Methodology

The Theory of Constraints (TOC) provides the most effective answers to today’s urgent questions. I’m glad to be working with companies that have already embraced TOC principles, as they are now tackling new challenges more smoothly and successfully.

Today, leaders must make decisions that may determine the fate of their businesses—as well as their own and their employees' futures. On the one hand, these decisions must be made quickly; on the other, they carry significant risks.

How can speed and risk reduction be balanced?

For those with even basic TOC knowledge or those interested in applying this powerful tool in today’s real-world situation, I offer a few solutions.

Basic Recommendations

This is a time when traditional accounting calculations cannot provide management with the data needed for quick and accurate decision-making. In fact, relying on such information may lead to poor decisions.

- Product profitability and cost calculations are now meaningless. A company producing only highly profitable products can still go bankrupt in a few weeks.

- Even an up-to-date profit and loss statement (if one can even be produced quickly) is useless. For instance, large inventories of finished goods and materials might need to be revalued at zero, rather than their defined or purchase price.

However, TOC’s decision-making technique, Throughput Accounting (TA), works flawlessly in this situation.

Even better, collecting the data required for TA decisions is simple. Any company can do it in minutes, even on a daily basis!

This involves tracking:

- S (Sales Revenue) and TVC (Total Variable Costs)—costs of purchased raw materials

- T (Throughput) = S - TVC

- OE (Operating Expenses)—tracked against prior periods

This provides management with all necessary real-time data for daily decision-making!

Different Business Scenarios

Each business is in a unique situation, which may fall into one of the following categories:

A. Business is closed or unable to operate due to external factors (government restrictions, loss of customer flow).

B. Business faces serious market constraints (customers cancel or reduce orders significantly, or clients fall into category A).

C. Business has no drastic order drop but faces supply chain disruptions (material shortages, transport or service restrictions, staff illnesses, self-isolation).

D. Business experiences a surge in orders but struggles with capacity (possibly due to supply chain disruptions or internal constraints).

Recommendations for Businesses in Category D:

- Apply the Five Focusing Steps (5FS) immediately to increase the system’s constraint throughput and maximize revenue (T).

- Accelerate internal cycle times (LT) to meet demand faster.

- Do not worry about rising material costs (Delta TVC), but adjust pricing if necessary, possibly through market segmentation.

- Consider reducing supplier payment terms in exchange for discounts—many suppliers face cash flow crises.

- If OE (Operating Expenses) increases but generates a positive Delta T - Delta OE, it is worth it.

- Monitor Free Cash Flow (FCF) and analyze the supply chain’s health.

IMPORTANT: Analyze the entire supply chain and buffer (BM) levels.

Be aware of the "Rebound Effect." If demand has surged, all supply chain participants may overorder, creating artificial demand spikes (Peter Senge’s "Beer Game" principle).

For example, if you manufacture buckwheat, demand may suddenly vanish in 2-3 months as excess stock builds up, leading to price wars and discounts. Prepare for this scenario today!

Recommendations for Businesses in Category B:

Your main problem is cash flow. Track FCF (Free Cash Flow) daily:

FCF = T - OE - Delta I

or

FCF = S - TVC - OE - Delta I

where:

- S = Total revenue (cash received)

- TVC = Money physically paid for raw materials

- Delta I = Investments (or cash gained from selling assets/inventory)

- OE = Operating expenses (rent, utilities, salaries, services, etc.)

If FCF is declining, calculate how long you can last before requiring external funding or transitioning to scenario A.

Recommendations for Businesses in Category A:

Your business is non-operational, but cash flow is still an issue. If there’s no revenue (S) and no direct costs (TVC), then:

FCF = Delta I - OE

If FCF is negative, determine how long you can sustain operations before bankruptcy or selling the business.

At this point, all available government support measures should be considered (wage subsidies, loan deferrals, financial aid).

Recommendations for Businesses in Category C:

Your business is in a "relatively normal" situation. You’ve faced similar challenges before. However, external conditions are different this time, affecting both you and your competitors.

This means new opportunities exist—but so do potential pitfalls. It’s up to you to decide how to respond.

You’ll find answers in TOC principles, particularly Throughput Accounting (TA), Load Time Planning (LTP), and Unrefusable Offers (URO).

This material is intended for specialists with at least basic knowledge of TOC. If you need to learn more, visit www.toc.lv.

For practical questions or online consultations, contact info@b4b.com.lv or georg@toc.lv.

Georgijs Buklovskis